The Human Cosmos | Part 3

Our Earth Reframed

What Does Space Teach Us About Planetary Thinking?

The Questions That Haunt Human Futures

What happens when humanity is no longer alone? Who owns first step, first land, first contact? What does citizenship mean if the human species becomes just one of many in a broader cosmic network?

These aren’t just science fiction musings, they are design questions about how society, governance, and culture might adapt to realities we cannot yet fully imagine (Sagan, The Cosmic Connection, 1973; Kaku, The Future of Humanity, 2018).

The Cosmic Connection | Carl Sagan

Ownership and Governance in Space

The United Nations’ 1967 Outer Space Treaty outlined an agreement that no nation can claim sovereignty over celestial bodies, framing space as “the province of all mankind.” Yet today, with the rise of private space enterprises like SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Axiom Space, the question of who controls first contact, or even the exploitation of extraterrestrial resources, is increasingly urgent. If a private company rather than a nation were to initiate first contact, what frameworks would ensure accountability, ethics, and representation for all of humanity?

Citizenship Beyond Earth

Citizenship has always been tied to land, borders, and states. But what happens when human life extends into orbit, lunar settlements, or Martian colonies? Will “Earth citizenship” become a unifying identity, or will new divides emerge based on planetary location or access to space technology? Scholars like Kathryn Denning argue that preparing for extraterrestrial life also requires us to rethink terrestrial inequalities, otherwise, we risk exporting the same hierarchies and exclusions beyond Earth.

The Psychology of Contact

Equally complex is the psychological dimension. How do societies respond when confronted with the knowledge of another intelligence? Research by the SETI Institute suggests reactions could range from profound unity to destabilising fear, depending on cultural narratives and political context (SETI Institute, 2021). In 2018, the Journal of Astrobiology published findings indicating that most people imagine discovery as positive, but governments and institutions remain cautious about the societal fallout. The challenge is less about if we encounter life, but how prepared we are to absorb its implications.

For designers, strategists, and futurists, these uncertainties are not abstract. They shape how we prototype governance systems, model ethical frameworks, and imagine cultural rituals for a future where humanity might no longer be the sole narrator of intelligence. The act of designing for these unknowns isn’t about predicting outcomes, but about preparing flexible systems that can adapt to which ever sceanrio emerges.

Mars Society Launches Global Campaign to Support Mars Desert Research Station

Designing Societal Structures from Scratch

Preparing for contact, whether with intelligent life, or simply with the realisation of our insignificance in a vast, living cosmos, requires us to build ethical and adaptable systems. This means interrogating our current resource ownership, national borders, human rights, and planetary governance. If outer space becomes an arena for expanded habitations, Earth will no longer be the only reference point for society.

Challenging Resource Ownership

At present, the Outer Space Treaty prohibits any nation from claiming sovereignty over celestial bodies, framing them as “the province of all mankind”. However, loopholes in this treaty have left room for ambiguity. For instance, the U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act (2015) allows American companies to own and profit from resources mined in space, raising questions about whether capitalism will dominate the extraterrestrial commons. Designing new frameworks means considering models beyond territorial ownership and perhaps stewardship or cooperative management systems inspired by Elinor Ostrom’s theories on governing shared resources (Governing the Commons, 1990).

Beyond National Borders

National borders have long defined identity, belonging, and conflict. Yet, as humans expand into orbit or planetary settlements, reliance on terrestrial nationalism could fragment rather than unite. The challenge is designing institutions that don’t just replicate the inequalities and power imbalances of Earth, but instead create frameworks for inclusive planetary citizenship.

If space becomes a domain for habitation or even cohabitation with other forms of life, human rights frameworks will need to adapt. Legal theorist Frans von der Dunk argues that current space law is overly state-centric and fails to protect individuals in extraterrestrial contexts (Space Law, 2015). For example, would freedom of movement apply between Earth and Mars? How do we prevent exploitation of workers in orbital or lunar industries? Designers and policymakers must collaborate to extend concepts of dignity and justice into environments where Earth is no longer the central reference point.

Designing societal structures for the unknown means breaking free from Earth as the sole anchor for political, legal, and ethical frameworks. Just as the Copernican revolution forced humanity to rethink its place in the universe, the possibility of extraterrestrial contact demands a new “cosmic perspective.” Carl Sagan argued that such a perspective fosters humility and empathy (Pale Blue Dot, 1994). For designers, this becomes not just a philosophical stance but a practical challenge, to build institutions that are scalable, inclusive, and capable of operating within a universe where humans may not always be the centre.

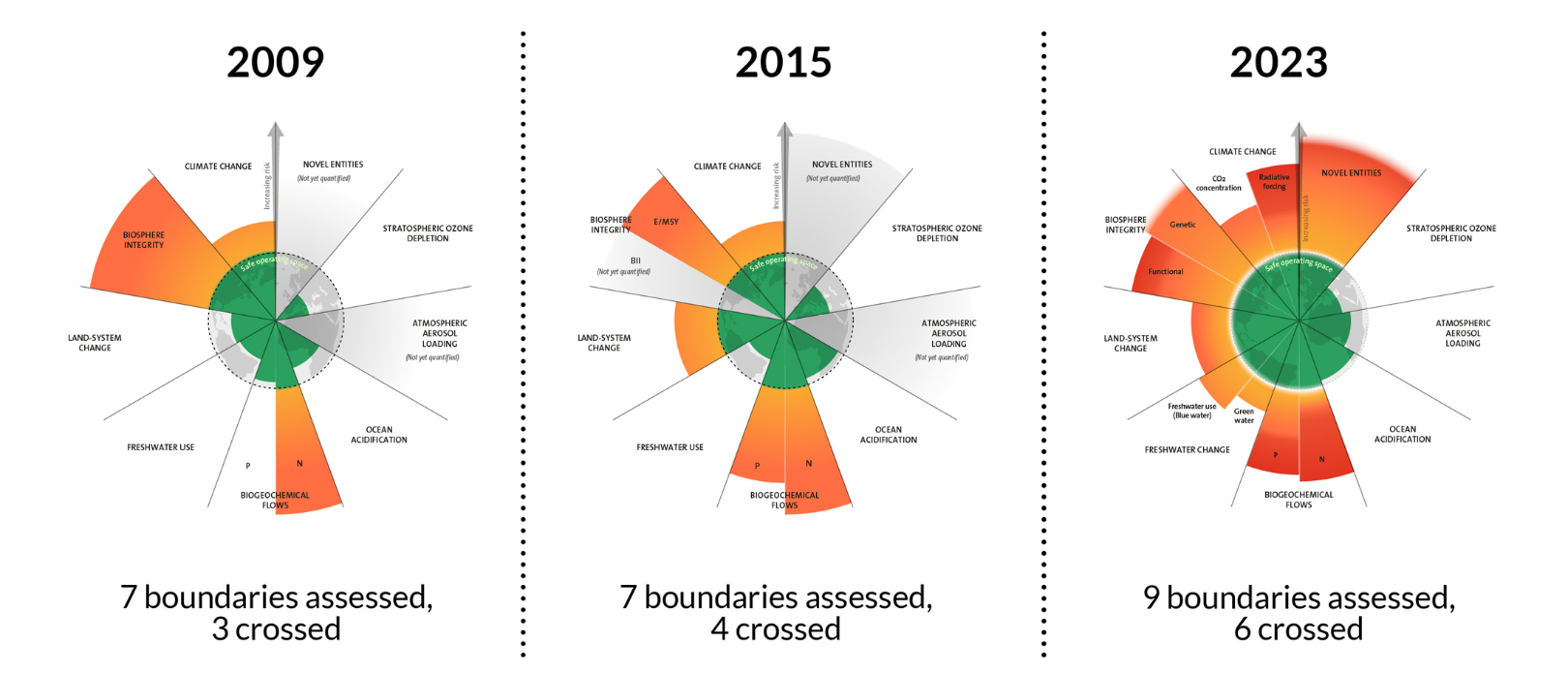

Planetary Boundaries | Stockholm Universities

Our Role in a Multi-Planetary Age

Space discovery doesn’t just change what’s out there. It changes how we see ourselves here on Earth. The accelerating urgency of climate change, biodiversity collapse, and resource scarcity highlights that humanity is already living within planetary limits. Johan Rockström’s work on Planetary Boundaries (2009, Nature) underscores that we are breaching critical thresholds that destabilise Earth’s life-support systems. Recognising these boundaries is no longer optional. It is essential to sustaining our way of life on earth or out there.

“The planetary boundaries framework highlights the rising risks from human pressure on nine critical global processes that regulate the stability and resilience of the Earth.”

At the same time, space exploration reframes us as planetary citizens rather than fragmented nation-states. Initiatives such as the Earthrise photo taken during Apollo 8 (NASA, 1968) or Carl Sagan’s reflection on the Pale Blue Dot (1994) have historically shifted collective consciousness, reminding us of our shared fragility and interconnectedness. Today, thinkers like James Lovelock with the Gaia Theory (1979) and more recent frameworks like the Doughnut Economics model by Kate Raworth (2017) push us toward systemic, regenerative models of stewardship that transcend borders.

This reframing carries a double challenge. First, to address the planetary crises already unfolding, through regenerative design, circular economies, and governance structures that recognise ecological interdependence (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2019). Second, to prepare ethically and sustainably for a multi-planetary future, where Mars colonisation projects by SpaceX and lunar resource extraction initiatives (e.g., NASA’s Artemis Program, ESA’s Moon Village concept) risk repeating Earth’s exploitative patterns if not carefully guided by cooperative planetary governance.

Ultimately, the challenge is not escape but regeneration. Space exploration should not be an excuse to abandon Earth but an invitation to radically rethink our obligations to it. Becoming multi-planetary must begin with a deeper commitment to ensuring Earth thrives, even as we extend into the stars.

Facilitated Co-Creation Workshop

Co-Creating Human Futures Beyond Earth

No single organisation, government, or culture holds all the answers to the profound changes space and cosmic discovery bring. The future must be co-created across disciplines, geographies, and lived experiences.

In my work I’ve seen how co-creation brings diverse voices, scenarios, and needs into the heart of innovation. By applying these principles to contexts as uncharted as orbital communities, inter-species diplomacy, or regenerative space infrastructure, we can design systems that are not just technically capable, but ethically grounded and emotionally intelligent.

Among the most powerful tools we have is collective intelligence. Bringing people together to share insights, assumptions, fears, and hopes might not bring the final answer, but certainly stimulates conversations, initial starter thoughts, and ideas. In many of the projects I’ve led, blending qualitative ethnographic insight with quantitative forecasting has helped organisations not just anticipate change, but empathise with the human challenges it brings. Translating that same approach to cosmic-scale questions means designing for empathy, adaptability, and shared purpose.

As design scholar Daniela Christian Wahl notes in Design for More-Than-Human Futures, the shift we need is from human-centred design toward planet-oriented and cosmopolitical systems, those that include non-human entities, ecosystems, and interdependencies in their logic and language ResearchGate. It's this expansive empathy that offers a true compass for navigating contact. Not merely with other life, but with alternate futures we are only beginning to imagine.

If we build together with intention, humility, and collective wisdom, our cosmic journey can be as human as it is extraordinary.